March 2024

At Picton Point in Pembrokeshire the tidal sections of two of West Wales’s best-known rivers come together to form the Daugleddau (or “two Cleddaus”). Their 27km combined estuary is also known as Milford Haven. Nowadays dominated by the oil and gas industry, this deep, natural harbour has been used as a port for hundreds of years.

The name “Cleddau” is derived from the Welsh word for sword (cleddyf) and is thought to be descriptive of the way the two rivers have carved their way through the landscape of West Wales. At the end of the last Ice Age, a surging river Teifi was temporarily blocked from its natural westerly course and instead flowed in a more south-westerly direction, gouging out what is now the Western Cleddau’s deep valley.

At around 50km in length, the Western Cleddau flows generally south through Wolfscastle and Haverfordwest, where the tidal section begins. The Eastern Cleddau rises at Blaencleddau near to Mynydd Preseli, flowing in a generally south-western direction for around 40kms to Picton Point. Its major tributary, the Afon Syfni flows out of Llys-y-Fran reservoir.

The north shore of the tidal Eastern Cleddau showing its confluence with the Western and with Picton Point in the far right of the photo.

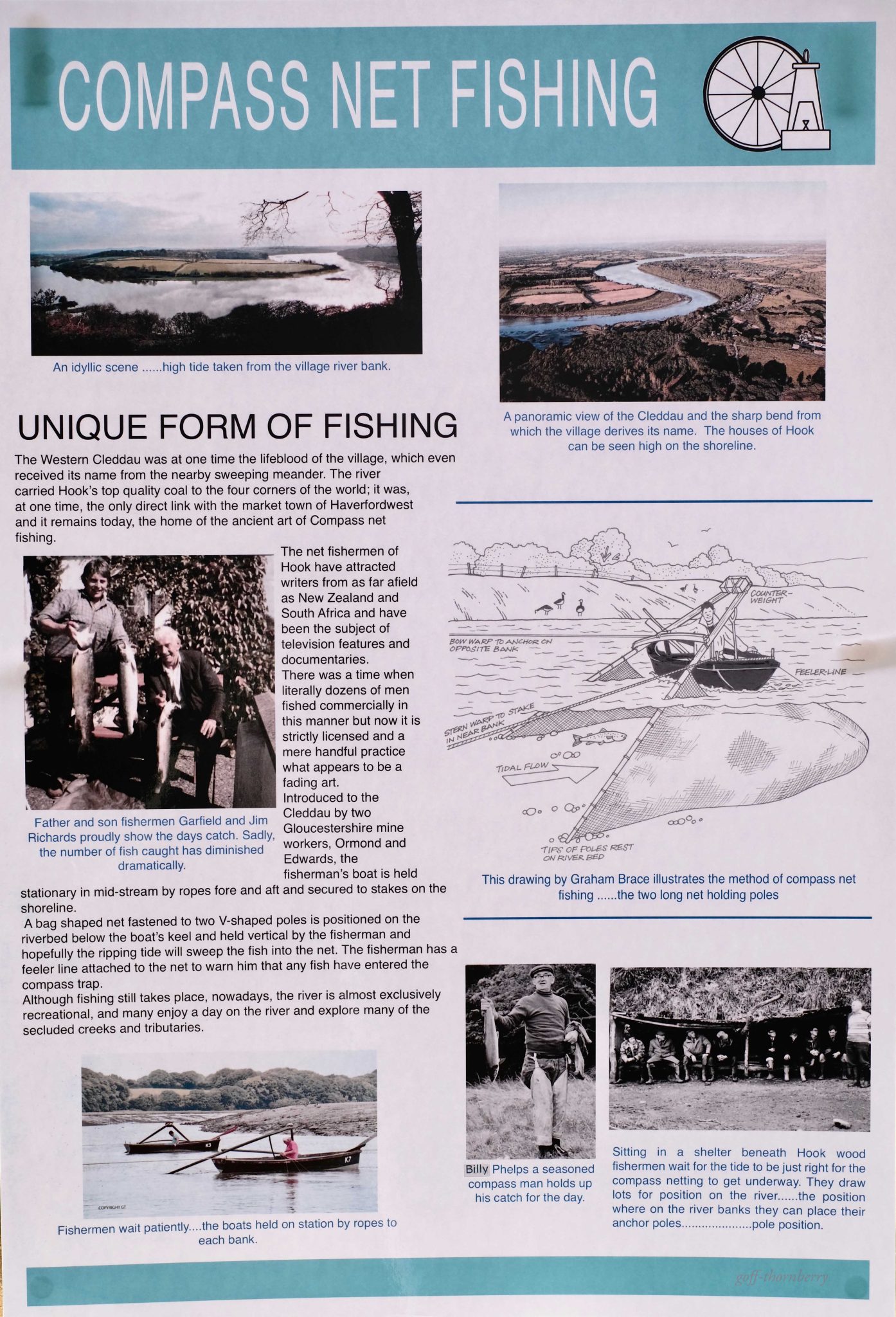

An exhibition board showing the unique Compass Net fishing technique at Hook (click to expand). Image courtesy of Hook History Society via People’s Collection Wales.

A colour postcard of a Llangwm Fisherwoman standing by a river from around 1900. Image courtesy of Thelma Gauden via Llangwm Local History Society/People’s Collection Wales.

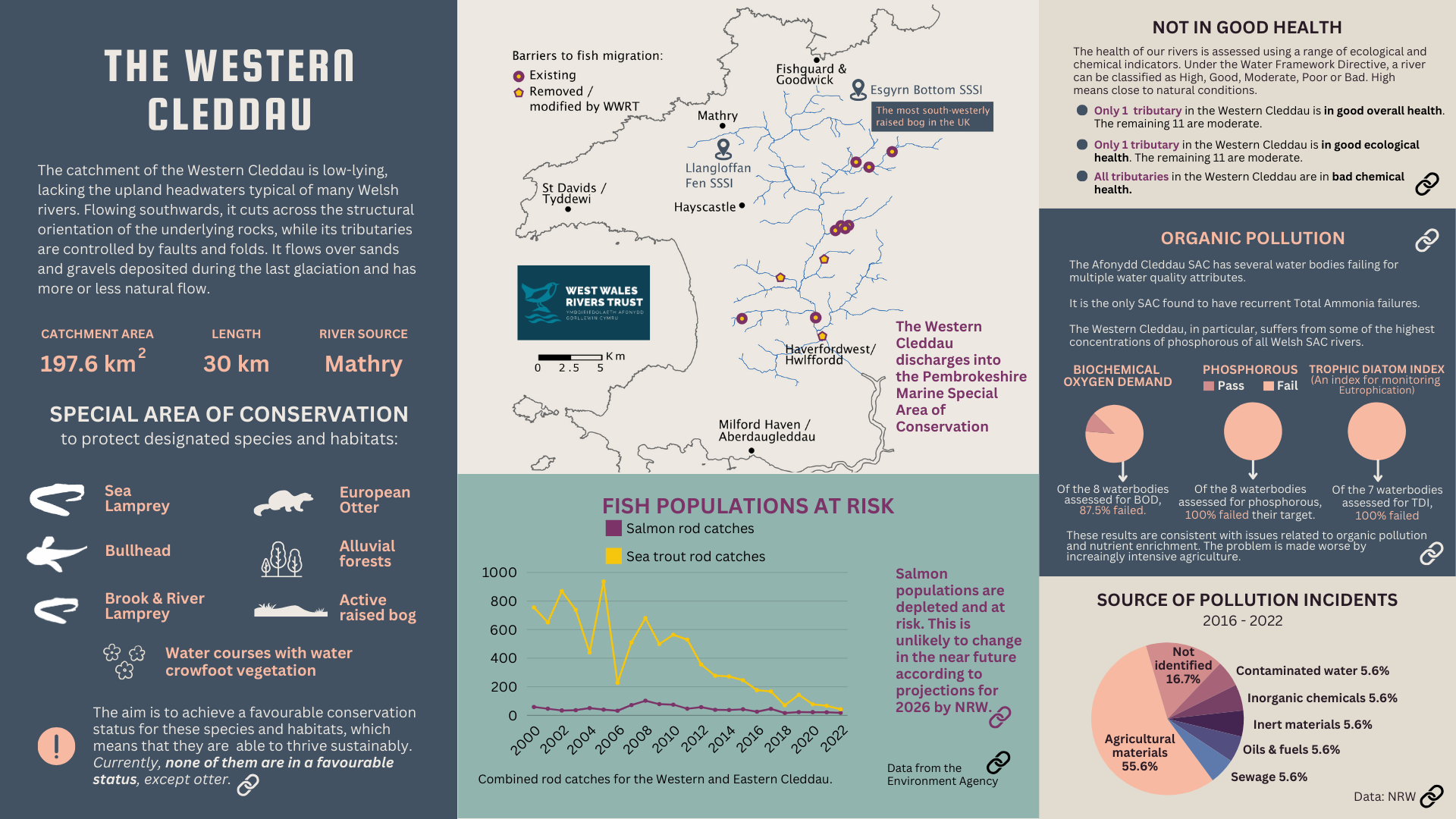

Factsheets for the Eastern and Western Cleddau (click to download).

Upper reaches of the Eastern Cleddau.

Both Cleddaus are Special Areas of Conservation (SACs), designated for many species including sea, river and brook lampreys, otters and water-crowfoot and habitats such active raised bogs and Alder woodlands. Both are also Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs).

The rivers, their estuary and the Pembrokeshire coast were once famous for abundant fish stocks and a successful fishing industry, along with the associated heritage. In the villages of Llangwm and Hook, near to where the two Cleddaus meet, a unique” Compass net fishing” style of catching salmon and sewin was developed.

But Llangwm has a much more curious claim to fame. Settled by displaced Flemish and English migrants after the Norman Conquest, the village had developed a thriving fishing industry by the 1800s, mainly supported by the huge shoals of herring just off the coast but also closer-by oysters, salmon and sewin. What was highly unusual, perhaps even unique in the British Isles at the time, was the village’s matriarchal society. Fishing duties, including rowing and navigation were shared between men and women but it was women who hauled the catches to markets in Haverfordwest, Pembroke and Tenby, dressed in their distinctive clothes. Unlike everywhere else during that period, women controlled the commerce while Llangwm’s men remained at home on “domestic” duties.

In something of a bitter toned anti-Suffragette article in 1908, the Pembrokeshire Herald suggested that this reversal of traditional roles could be explained by simple economics:

“…..the Llangwm fisherwife tramps miles through the county with her donkey and panniers, selling her fish or oysters as the case may be. In her quaint distinctive dress, short sleeved bodice, and short skirts, generally scarlet, the whole crowned by a “parson’s hat,” which may or may not have formerly adorned the head of the rector of the parish, the Llangwm fishwife is quite a character, and her visits are looked forward to by the housewives of the county. Anyhow she draws infinitely more custom than her man would do.”

Herring numbers had begun to decline on the Welsh coast at the time of the article. And, like many other rivers, over-exploitation of salmon stocks by humans was also causing steep declines in catches. Before then, the Cleddaus had been renowned for their runs of salmon and sewin. In 1834 George Agar Hanson remarked that the two rivers “….though narrow and shallow, are penetrated up their sources by vast quantities of salmon and sewin during the spawning season.”

This was not to last. The extensive netting of upstream migrating adults in addition to juveniles heading downstream to sea, as well as removal of salmon from the spawning grounds had begun to take its toll by the end of the 19th century. Something called “the great net” which had been used in the Teifi estuary but had been declared illegal, was reported as instead deployed in Milford Haven in 1887, catching 2,000 fish that year. According to angling reports in the early 1900s, where the Cleddaus had once “abounded in fish”, they had now “gone to pot.”

Controls on netting meant that salmon and sewin stocks were to recover. In 1970, over 350 salmon and over 600 sewin were caught by anglers from the two rivers (250 salmon were considered a good year in the late 1800s). Since then, however, numbers have declined once more and in 2022, a rod catch of only 17 salmon and 43 sewin was recorded. NRW now assess the river’ stocks as “at risk of extinction” and predict them still to be at risk in 2026.

What are the current issues affecting the Cleddaus?

While they face the usual issues of rivers across Wales, including barriers to migration and the effects of climate change, pollution is now the primary concern on the two rivers and that intensification of agriculture has been the main cause, particularly dairy farming (and associated industries) and slurry spreading. Worryingly, increasing numbers of intensive poultry unit applications are now also being submitted in this part of Wales.

The data tells the story. The Western Cleddau is now the worst performing of all Welsh SAC rivers for phosphorus with all eight of its waterbodies failing their targets. Between 2016 and 2022, 56% of the river’s pollution incidents were attributed to agriculture, with only 6% down to sewage discharges.

The Eastern Cleddau’s water quality has shown some even more concerning results. According to NRW, of the substantiated pollution incidents between 2016-2022, 72% were attributed to agriculture with slurry being the primary pollutant. The river is also the only SAC in Wales to have recurrent Total Ammonia failures and the only river to have failure for “unionized ammonia”, the form most harmful to fish.

What’s the current issues on the Cleddaus?

History tells us that rivers in Wales can recover, even from seemingly hopeless situations. And efforts are underway in the Eastern and Western Cleddaus to resolve their issues.

The West Wales Rivers Trust has delivered a considerable amount of work restoring access for migrating fish. However, they have also been running their innovative “Adopt a tributary” scheme, whereby local volunteers take responsibility for being the eyes and ears along a particular section of river. This provides essential information on the health of streams to the trust, who otherwise would not be able to cover such a vast catchment. The volunteers record evidence on a survey app, which then feeds into a central database and is used by the trust to prioritise areas and work. The volunteers also undertake other restoration activities such as litter clearances and invasive species removal.

A common characteristic among the few healthy or recovering rivers in Wales are strong community-based initiatives to compliment the work of river trusts. The newly formed Save the Cleddau Project is one such initiative. Its inaugural meeting was held in January this year and funding is now being sought to launch C-CAP (Cleddau Catchment Assessment Project) – a major Citizen Science water testing project in conjunction with the Adopt a Tributary initiative.

West Wales Rivers Trust have been working hard to restore section of the Cleddau, including habitat enhancement work such as that shown above. Here the Western Cleddau a few miles upstream of Haverfordwest has been fenced off, protecting its banks from grazing livestock. The maximum benefit of efforts by the trust and local volunteer groups will only be realised if they are backed up by effective enforcement of agricultural regulations by Natural Resources Wales.

The valiant efforts of the trust and volunteers need to be as effective as possible to turn the tide. However, this will be reliant to a large degree on Natural Resources Wales enforcing agricultural regulations effectively.

For too long, the sector has enjoyed light-touch regulation, allowing it to become the largest contributor to water quality problems in SAC rivers in Wales. Our regulator must focus on what only it can do and be bold. When it comes to pollution, for too long we have heard its mantra “prosecution is a sign of regulatory failure.” Almost everyone else believes that it is in fact the pollution that is the sign of regulatory failure.

Our thanks to the West Wales Rivers Trust for their help with information and photos.

References & More Information:

“The Cleddau Project – Restoring the health of our waterway from source to sea.”

Afonydd Cleddau/Cleddau Rivers – Designated Special Area of Conservation (SAC). JNCC

Western Cleddau SSSI Sitation, Natural Resources Wales.

Eastern Cleddau SSSI Citation. Natural Resources Wales.

West Wales Rivers Trust “Afon Syfynwy INNS survey.” 2022

“Salmon and Sea Trout Rivers of England and Wales” Augustus Grimble, 1904.

“Trout and salmon fishing in Wales.” George Agar Hansard, 1834