June 2024

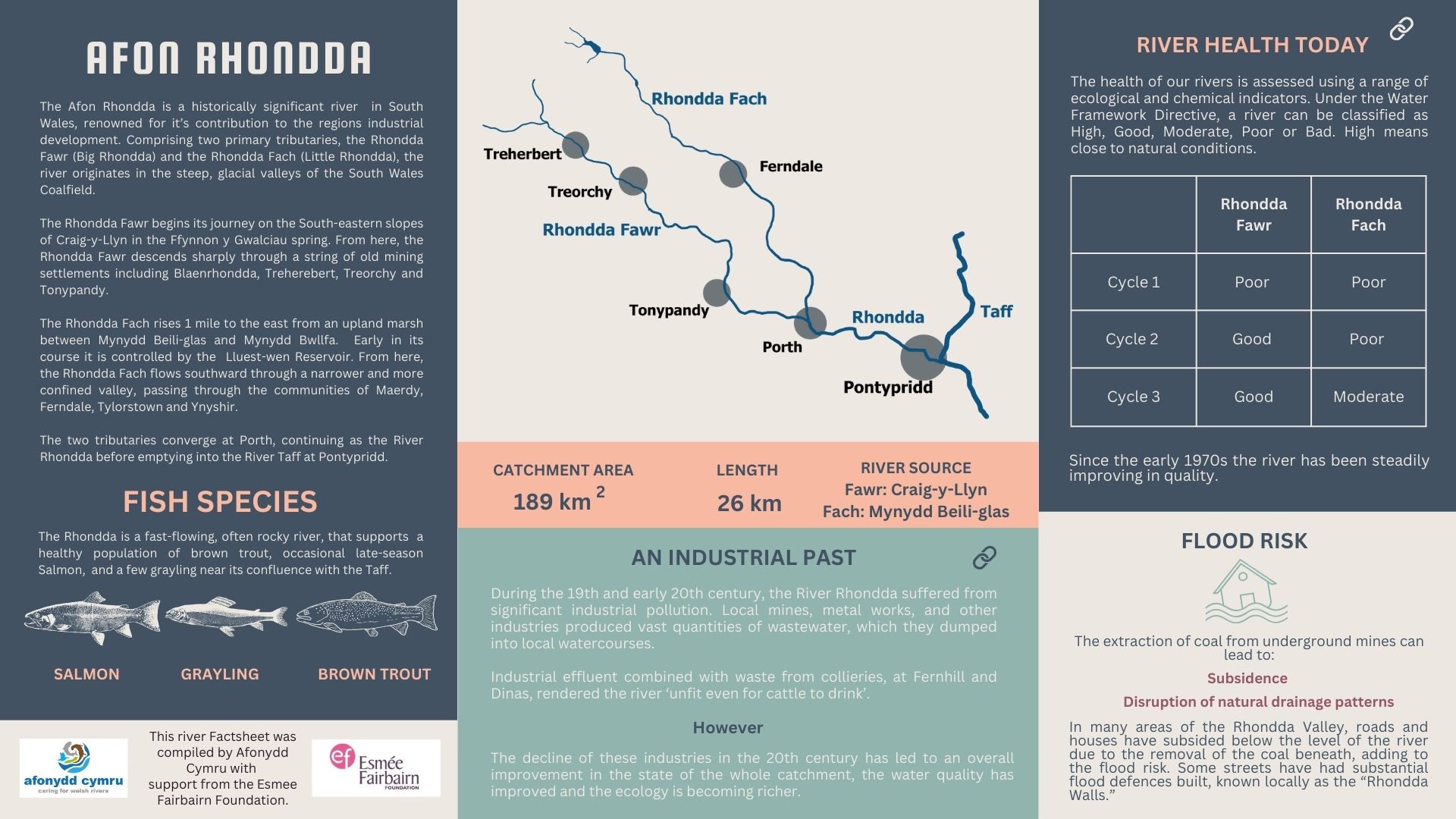

From the high plateau of Blaenau Morgannwg in Glamorgan, the two deep and steep-sided glacial valleys drop sharply to the south east in the direction of Wales’s capital, Cardiff. Within them flow two of the South Wales’s familiar rivers, the Rhondda Fawr and Rhondda Fach (“Big” and “Little” Rhondda respectively).

At the town of Porth, the Fawr is joined by the more northerly Fach, after which the main Rhonnda continues on its south easterly course for another 6km before it enters the Taff at Pontypridd. The name “Rhondda” is thought to refer to the noisy sound of its water, similar to the English term “babbling brook.”

Downloadable Rhondda factsheet

A stone bridge spanning the upper Rhondda Fach at Bryn Du, a few miles downstream of Lluest-Wen Reservoir. It is said to be the oldest surviving bridge in the Rhondda Valley.

Failure of flood defences in Gelli, a village on the banks of the Rhondda Fawr in the mid 1960s.

The village of Ton Pentre, through which the Rhondda Fawr flows,with the coal tips on Mynydd y Gelli in the foreground. Prior to coal mining, the landscape would have been mostly covered in forest.

Human history in the Rhondda Valleys is thought to date back to prehistoric times, possibly as early as 4400BC. At the head of the Rhondda Fawr is the iron age settlement of Hen Dre’r Mynydd (“the Old Settlement on the Mountain”) while at Fernadale on the Rhondda Fach are the remains of Twyn-y-briddallt, a Roman marching camp used in their attempts to subdue the Silures in around AD50. In 1326, Edward II was said to have taken refuge in the Rhondda Valley before his eventual capture and relinquishment of his crown a year later.

However, common with most of the rivers in this part of Wales, the most significant anthropogenic changes to the Rhonddas came during the industrial period, and from coal mining in particular.

According to The Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian, there were seven collieries operating in the Rhondda Valleys by 1846. The industry expanded most rapidly after 1855 and, despite its mines gaining a reputation for horrific accidents, the output of the Rhondda coalfield was at its peak in 1913 extracting over nine and a half million tonnes of some of the best quality coal in the UK. With it came the associated rise in the human population, from a few thousand in the first half of the 19th century to over 160,000 by 1920.

Industrial pollution

The effect on the area and rivers was inevitable. Like many other rivers in south east Wales, the Rhondda often ran black from mine discharges. But coal was not the only polluting industry. In the late 1800s newspapers were reporting that “a vile and abominable mess of yellow colour” from tinworks “stained” the river. Together with the mine pollution, this had made the water “unfit even for cattle to drink” compared to before industrialisation, when the Rhondda had run clear. Sewage pollution was also causing health problems at that time, with reports in the press of regular outbreaks of typhoid among the local population.

A physical change to the landscape at this time was also underway. As late as 1883, the Rhondda Valley was reported as being largely afforested. The names of many of the towns and villages also allude to this, including either “coed” (wood) or “gelli” (grove). With the expansion of coal mining came an unquenchable thirst for wood to make pit props. The result was the wholescale deforestation of the area, a situation that has been partly rectified now through Natural Resources Wales forestry planting.

Rhondda Walls

Without detailed records, we can only speculate what the effects of this change to the landscape in the 19th and 20th century would have been in terms of the Rhondda’s water quality and just as importantly, the flood risks to nearby towns. And in many areas of the Rhondda Valley, roads and houses have subsided below the level of the river due to the removal of the coal beneath, adding to the flood risk. Some streets have had substantial flood defences built, known locally as the “Rhondda Walls.”

By the 1920s the coal industry began to decline with the last remaining Rhondda mine, Maerdy Colliery, closing in 1990. And in contrast with many rivers in Wales, the river’s water quality has been improving since then. Water Framework Directive Assessments carried out by Natural Resources Wales now classify two out of the three Rhondda waterbodies as “Good Ecological Status” and overall health. Wild brown trout are reported as thriving in the river with water quality-sensitive grayling present in the lower reaches too.

Monsters and beasts

The river is home to a range of other wildlife too, with community organisations such as the “Rhondda Valleys Wildlife and Nature Group” using social media to celebrate its natural wealth.

One of the legacies of the coal mining era are the numerous spoils sites that litter the south Wales valleys. While these can pose a threat to towns and river ecology (in 2020 60,000 tonnes of coal waste slid into the Rhondda at Tylorstown), they have also becoming an increasingly important habitat for some very rare species. Two types of millipede, one thought only native to the Pyranees (named the “Maerdy Monster”) the other a new species entirely (the “Beddau Beast”) have been found by entomologists in the Rhondda Valley recently.

Following the success of a similar project on the nearby Afon Cynon, South east Wales River Trust have now extended their “A River For All” initiative to the Rhondda. This project engages local people – adults and children – in river monitoring and restoration, including litter clear ups, invasive species management and invertebrate sampling.

References & More Information:

South East Wales Rivers Trust, A River For All

“Vitriol in the Taff: River Pollution, Industrial Waste, and the Politics of Control in late Nineteenth-Century Rural Wales.” Keir Waddington, Cambridge University Press 2018.

“A slagheap safari in Wales – The hills are alive with rare plants and bugs.” CIWEM, 2023

Waterwatch Wales. Natural Resources Wales

“Historic Landscape Characterisation The Rhondda. The Rhondda Historical Processes themes and background.” Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust & Cadw

“Great Archaeological Sites in Rhondda Cynon Taf.” Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust & Cadw.

Rhondda population growth – A Vision Of Britain Through Time.