December 2023

On an autumn evening in 1880 a riot broke out in a town in mid-Wales. Such was its ferocity that one man was reported lucky to have escaped with his life.

The cause of the unrest? Atlantic salmon. Not their scarcity or impending extinction but instead a prolific abundance and, specifically, the attempts by water bailiffs to prevent the inhabitants of Rhayader from taking their share of the natural bounty from the nearby river Elan.

1880 was a year of some spectacular poaching incidents in the area. On that November night the “Rebecca Riot” as it was described in the press (named after a period of rural conflict earlier that century) involved a gang of 68 poachers removing around twenty salmon from the Elan, supported by a crowd of locals. And a few days later, about 100 “Rebeccaites” were reported to have been spearing salmon in the Wye (of which the Elan is a tributary). Fearing brutal repercussions, local bailiffs and police stood by as the fish were removed, probably a wise move considering one man with the courage to express disapproval was taken to hospital with broken ribs.

Earlier that year the Cambrian News reported another large-scale after dark poaching event in January:

“Every ford on the river Elan was fished, and a great quantity of salmon captured. The poachers are said to have openly wheeled the fish through the streets of the town and sent them off in cartloads.”

A salmon poaching gang working a river in the upper Wye catchment (probably in the early 1900s).

With its source high on the moors of Ceredigion (known as Elenydd), the Afon Elan once flowed over a twenty-five mile south easterly course to join the Wye a few miles downstream of Rhayader. Up to the 1890s, it is safe to say that the Elan was a prolific Welsh salmon river. In April 1892, however, that was not exactly the scenario put to MPs in Westminster by civil engineer James Mansergh, who had taken on the challenge of resolving Birmingham’s water supply problems.

At the time, England’s second city was running out of clean water. Its rapid expansion during the industrial period meant a burgeoning population was now suffering outbreaks of diseases normally associated with unsanitary water supplies: cholera and typhoid especially. The Western Mail reported that despite the poaching and riots, Mansergh told MPs that there was ““¦.practically no salmon fishing about the Elan, and but little spawning ground.“

It is unclear whether this was accepted as an accurate description but under pressure from the city’s council, Parliament passed the Birmingham Corporation Water Act in 1892, effectively allowing land in mid-Wales to be compulsory purchased to build dams and create a new water supply.

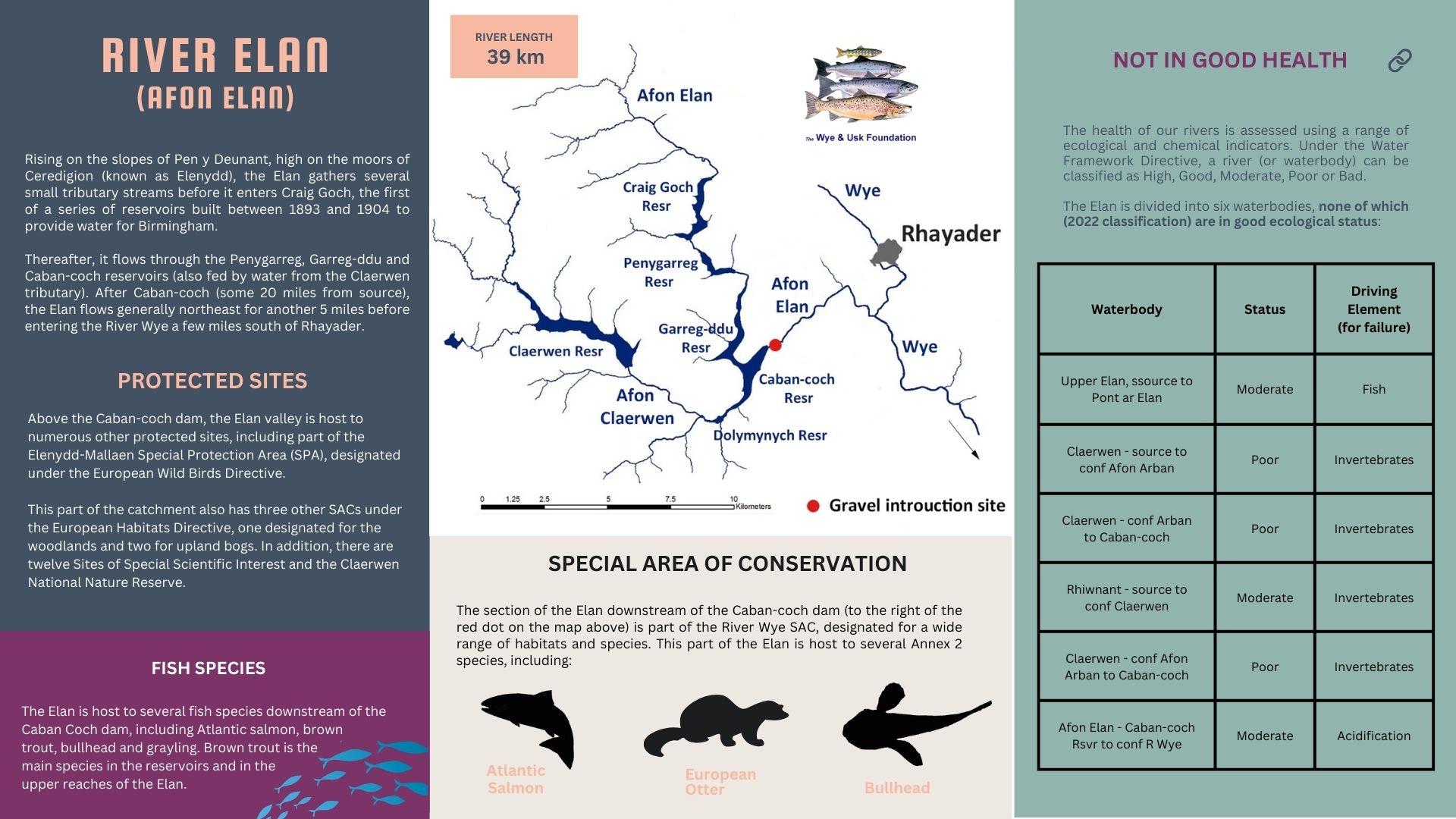

The Afon Elan

The very next year work began on the construction of a series of major dams along the Elan valley. And nine years later, on 21st July 1904, water that had previously been destined for Chepstow and the Bristol Channel began arriving 60 miles to the northeast, at the newly-dug Frankley Reservoir on the south west edges of Birmingham.

The Elan Dams and their aqueduct were a stunning feat of late-Victorian period engineering. However, for the ecology and wildlife of the Elan, this part of the Wye catchment had changed forever. In addition to fundamental alterations in geomorphology, chemistry and water temperature, the dams sealed off the Elan’s headwaters from Atlantic salmon who had previously used it as a spawning area and juvenile nursery area.

Despite Mansergh’s downplaying the environmental impacts in his pitch to Westminster, the dams’ likely effects on fish stocks of the Elan and Wye were acknowledged. Mitigation schemes for the lost spawning grounds included improving fish access to nearby tributaries and the setting up of a permanent fund paid for by the Corporation of Birmingham to improve Wye fisheries, a fund that is still in existence today and managed by Natural Resources Wales. In 1907, three years after the dams were completed, The Evening Express (a Cardiff newspaper) reported that:

“The River Elan, from its junction with the Wye right up to the Caban Coch dam of the Birmingham Waterworks, is literally teeming with salmon” and that by standing on one of the Elan’s footbridges, “”¦as many as fifty salmon may be counted in as many seconds.”

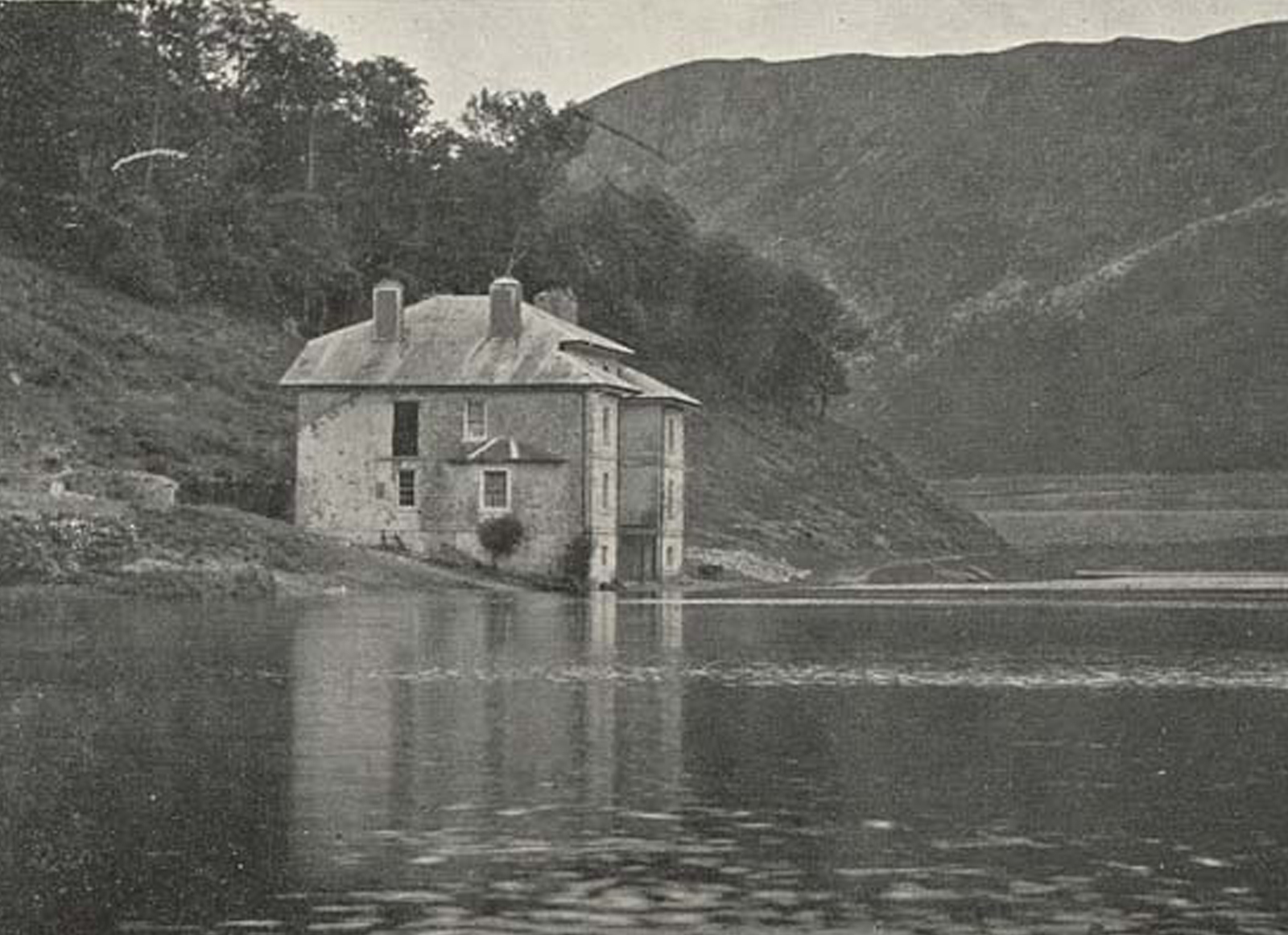

Work begins on the construction of the lowest of the Elan dams, Caban Coch, in 1892.

Cwm Elan, a house that the poet Shelley stayed at frequently but was lost to the rising waters after the dams were built. Used to house engineers during the construction phase, Cwm Elan was demolished before it was submerged.

The newspaper also reports an initiative by the Corporation of Birmingham to create artificial spawning beds below the lowest of the dams, Caban Coch. It estimated that over 500 salmon had become trapped between these weirs, unable to progress any further upstream. The artificial spawning beds were not to exist for long: in 1932 JA Hutton noted that salmon no longer spawned immediately below the Caban Coch dam and were now only to be found in very lowest reaches of the Elan.

By the start of the 21st century, the ecology of the Elan had become severely degraded. While the gravels in the 5 miles of river below Caban Coch had steadily washed downstream in their natural way, the dams had prevented any replacement. What remained was a river of bedrock and boulders, devoid of the sediments and fine gravels that are essential for fish and invertebrate life.

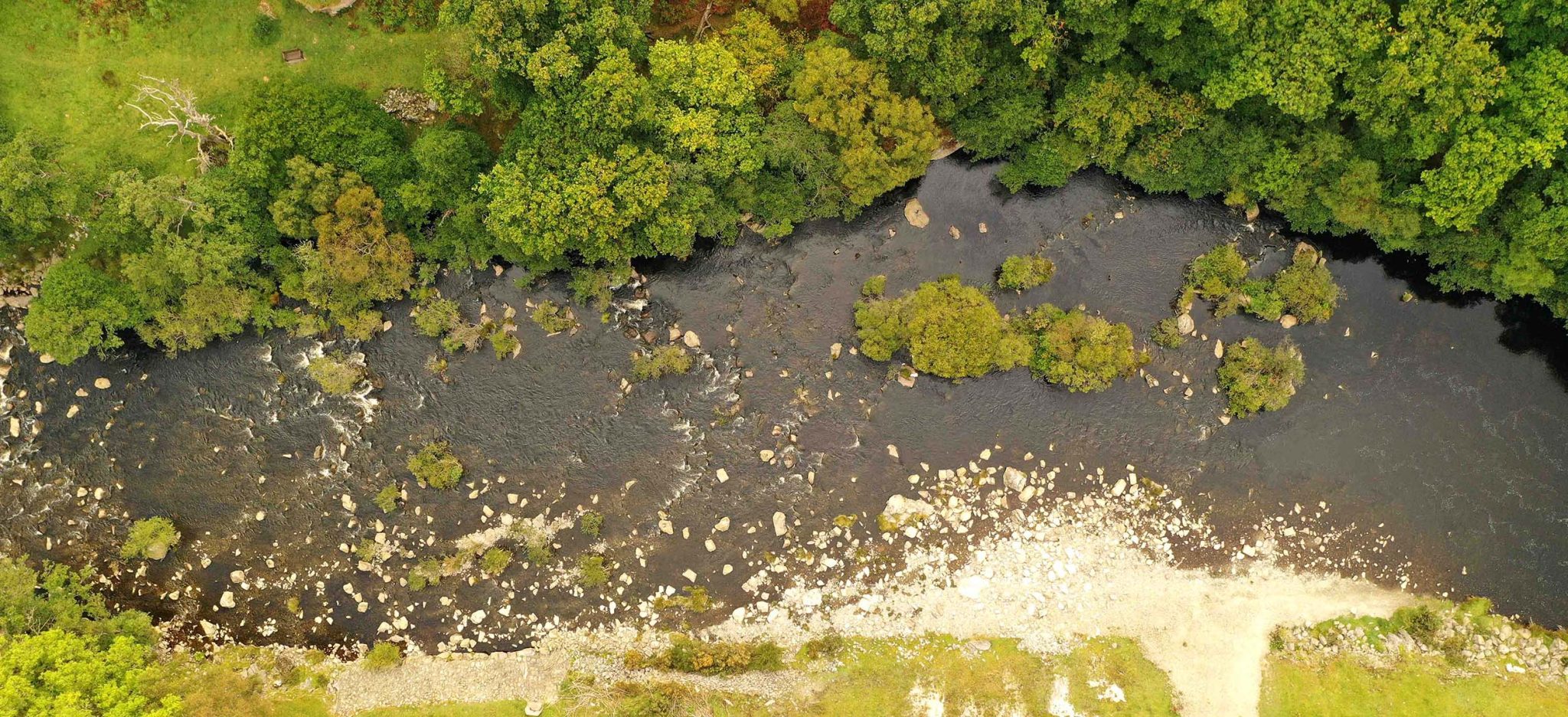

New gravel being introduced by the Wye & Usk Foundation to the Elan below the lowest dam. This gravel is stacked on the bank ready for the winter flows to distribute it naturally in the river.

Within four years of the Elan gravel replenishment project, juvenile salmon were recorded to have increased twentyfold. These fry were caught during electrofishing surveys in the Elan in 2017.

Downloadable Afon Elan factsheet

In 2016 a new initiative to replace the river’s lost gravels was launched by the Wye & Usk Foundation, Welsh Water and Natural Resources Wales. Thousands of tonnes of new gravel were introduced to the Elan just below the dams, sourced from sites on the upper Wye and the Elan further upstream. And the project showed almost immediate results. By 2020 and after four gravel replenishments, fish were beginning to return in numbers. Adult salmon were once again witnessed spawning just below the dams and electrofishing surveys had registered a twenty-fold increase in the number of juvenile salmon in the Elan. Invertebrate populations had begun to recover, as had other fish species (such as trout and bullhead) along with kingfishers and herons. The project’s success showed what could be achieved with gravel augmentation and led to similar initiatives on the Usk and Taff.

From the start it was predicted that the difficulty in building on and maintaining the project would always be in finding gravel source sites. Unfortunately, that prediction came to fruition. Despite the Elan upstream of the dams having large deposits of river gravels (as does its tributary the Claerwen) and it being the natural source for the river below, the area is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). Source sites have been shown to recover quickly but the risks to a SSSI of gravel extraction always need to be considered.

This has meant that instead of the required several hundred tonnes of gravel annually, the Wye & Usk Foundation have struggled to introduce half that amount of that in recent years. After the early successes, salmon numbers have fallen back, although not yet to the low numbers before the project began. Despite these difficulties, the Wye & Usk Foundation has soldiered on with the search for new, viable source sites. And with good reason: the Elan represents 7% of the salmon spawning area of the Wye and is becoming increasingly important for this beleaguered fish species. Provided the habitat is right, the controlled flows of the dams can provide them with some refuge from the extremes of temperature and flow as climate change takes hold.Â

The Elan’s importance to the Wye’s salmon does not end there. Even back in 1892 it was suggested that in addition to the dams’ mitigation fund, “”¦the supply for compensation water sent down the streams as now proposed should be very largely augmented.” However, it was not until 2016 and the implementation of recommendations from the Usk Wye Abstraction Group (UWAG) that releases from the Elan reservoirs began to help salmon and other fish species. Comprised of the Wye & Usk Foundation, Welsh Water, Natural Resources Wales and Canal & Rivers Trust, UWAG’s ground-breaking work ensured that water releases from the Elan dams aided salmon migration by releasing extra water to supplement summer spates that are vital for their journey upriver. Just as importantly, if the flows in the lower Wye dropped close to the minimum level required by salmon to enter the river, UWAG recommended extra water to be released to reduce estuary mortality.

Thanks to the work of the Usk Wye Abstraction Group, water is now released from Caban Coch to help salmon and other species in the Elan and Wye.Â

The success of UWAG cannot be underestimated. While their work was focused on salmon, there were benefits to the wider ecology of the Elan and Wye too. Such is the significance of these water releases that anyone unfamiliar with Elan and Wye standing at their junction during a dry summer would have difficulty knowing which was the main river and which the tributary.Â

In December 2023 the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) stated that global Atlantic salmon numbers between 2006 and 2023 decreased by 23% between and that the species was now endangered in the UK. It goes without saying that everything that can be done to protect them must be done. The days of cartloads of unlawfully caught Elan salmon feeding hungry local mouths may be long confined to history, but this river still has a significant role to play in the future survival of the species.

Our thanks to the Wye & Usk Foundation for their help with information and photos.

References & More Information:

“The Spawning Grounds of the Upper Wye.” JA Hutton, 1932

“Gravelling the Elan Project” Wye & Usk Foundation

“The Usk Wye Abstraction Group” Wye & Usk Foundation

Welsh Newspaper Article Archive, National Museum of Wales.