August 2024

On 11 December 1282 near Cilmeri in mid Wales, a soldier serving Edward I ran a Welsh combatant through with his lance. At the time Stephen de Frankton was unaware that the person he had just fatally injured was Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, the commander of the Welsh army that had just been defeated nearby at the Battle of Orewin Bridge (Irfon Bridge). On the edge of Cilmeri and close to the banks of the river Irfon a monument stands today marking the death of the last Welsh Prince of Wales.

The Irfon is one of the three major tributaries of the upper Wye. Rising on the slopes of Drygan Fawr to the west of the Elan Valley dams, the river flows south initially, passing the “The Devil’s Staircase” before turning into a steep sided valley named Camddwr Bleiddiad, or Wolves’ Gorge, claimed as the location where the last wolf in Wales was killed.

Camddwr Bleiddiad, or the Wolves’ Gorge looking up the Irfon towards the Devil’s Staircase.

The annual “world bog snorkelling” championships are held in the Irfon valley near Llanwrtyd Wells.

The Irfon upstream of the Devil’s Staircase. Commercial forestry in the Irfon’s headwaters have exacerbated the river’s water quality problems.

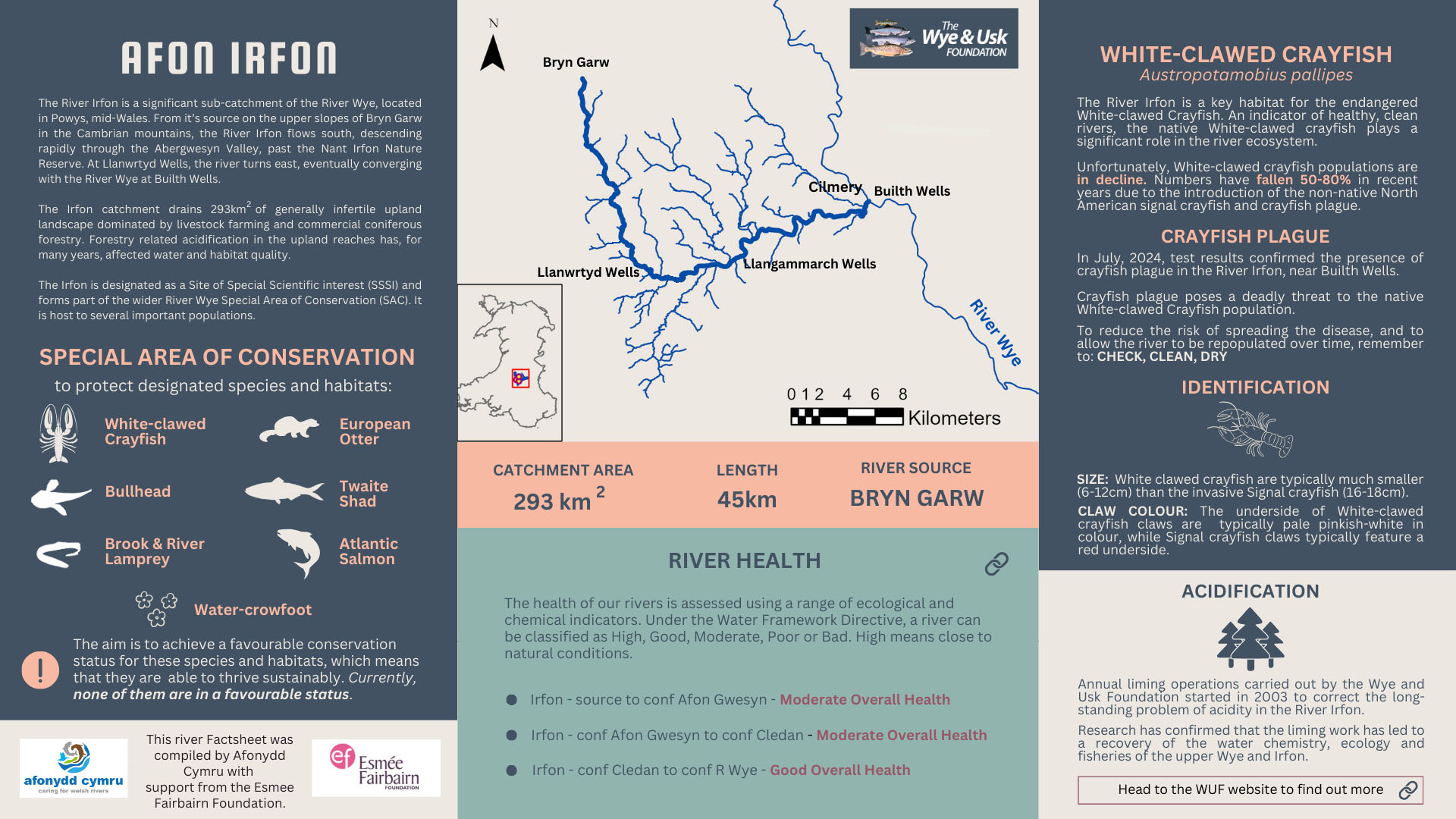

Downloadable Irfon factsheet

The native White-clawed crayfish and below, the larger, more distinctive American Signal crayfish. Â

From there the Irfon flows through Abergwesyn and Llanwrtyd Wells, the smallest town in Britain, host to the famous annual “Bog Snorkelling Championships” and “Man Versus Horse Race.” Flowing then in a more westerly direction, it then reaches Llangammarch Wells where, to continue a theme, the last wife auction in Wales is said to have taken place in a local hotel. Around 45km from its source, the Irfon joins the Wye at Builth Wells.

The river’s name is believed to come from the Welsh for fresh (“ir”) and river (“afon”), in tribute to the purity of its water. In 1732 local vicar Theophilus Evans claimed that the water from the river at Llanwrtyd had cured his scurvy. By Victorian times the three “wells” towns along its length were attracting large numbers of tourists who took the water from nearby springs to cure anything from gout to rheumatism and heart disease.

The ecology of the Irfon in those times was also very healthy, without the coal mining, heavy industry or large towns that destroyed the water quality of many Welsh rivers to the south. Atlantic salmon were abundant, as were brown trout, otters and a range of other species. A huge salmon of 45lb was reported caught in the Irfon in the early 1880s.

The Irfon’s decline

But by the end of the 20th century the river was in a poor state and no longer living up to its name. Severe flushes of acid were affecting the water quality in the upper reaches, wiping out the invertebrates that fed the river’s juvenile salmon and brown trout, even killing fish eggs buried in the otherwise pristine gravels and damaging the gills of adults. This and widespread habitat degradation meant that numbers of salmon were plummeting and the Irfon was no longer a refuge for the very large fish the Wye was once famous for.

Acid rain and a local geology that could not buffer it were the cause but also in the mix was the large increase in commercial conifer plantations in the Irfon’s headwaters, whose forestry drains removed what little ability the land had to soak up the acidity by flushing it directly into the river. The increased use of powerful, highly toxic insecticides such as synthetic pyrethroid were also to blame for the decrease in the water quality.

White-clawed crayfish

Salmon were not the only species to suffer. The river is host to other protected species that also depend on good water quality such as lampreys, bullheads and otters. Freshwater pearl mussels are present in the middle and lower reaches, as are White-clawed crayfish (Austropotamobius pallipes).

And like all invertebrates, the UK’s only native crayfish is also vulnerable to spikes in acidity and insecticides. While the Irfon remains an important home for native crayfish, there was a major retraction in their distribution and numbers between 1970 and 2010, just as the use of powerful sheep dips increased.

Breathing life back into the Irfon

In 2010 the Wye & Usk Foundation and its partners began a 4-year European Union LIFE+ funded (€1.27m) project to restore the Irfon and protect its rare species, including the native crayfish. Amongst a range of objectives, the Irfon Special Area of Conservation (ISAC) project involved liming the Irfon’s headwaters to nullify the acidic spikes, block some of the forestry drains to more “normalise” flows, improve habitat for fish and invertebrates and reintroduce native crayfish bred in Natural Resources Wales’s research facility near Brecon.

Work to restore the Irfon by the Foundation and others has continued since then but the ISAC project achieved some impressive results. The liming and drain blocking improved the ecology in the upper reaches while the habitat restoration work almost immediately increased numbers of juvenile salmon at improved sites by an average of 238%. Despite ups and downs since, numbers of young salmon remain relatively healthy in the Irfon. The 2024 electrofishing surveys have shown some particularly encouraging results.Â

The plague

Sadly, the same cannot be said for the White-clawed crayfish. In addition to poor water quality, the major threat to this species is the invasive American Signal crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus), introduced to Britain in the 1970s to be farmed. Not only does the invasive species out-compete, it also brings a disease commonly known as “crayfish plague,” which is usually fatal to our native crayfish.

Earlier this summer numerous dead White-clawed crayfish were found in the Irfon with Natural Resources Wales subsequently confirming an outbreak of plague. The public have been urged to stay out of the river and to follow “Check, Clean, Dry” protocols if entering other waterways in the area.

Hopefully, this is not the end of the crayfish and another “last” for the Irfon. While there are good reasons to feel positive about the river, this summer’s events show how important biosecurity is in the protection of rare species and just how fragile river ecosystems are.

References & More Information:

ISAC Project – Wye & Usk Foundation

ISAC Project, End of Project Report

The Vales of Irfon and Ithon – Natural Resources Wales

Deadly Crayfish Plague Suspected Near Builth Wells: Public Urged to Stay Out of River Irfon – Natural Resources Wales

Afon Irfon SSSI Citation – Natural Resources Wales

Llangammarch Wells History Society

White-clawed (or Atlantic stream) crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes – JNCC